FAVELA RESEARCH

Digital Activism, Community Community Policing, and Critical Pedagogies in Brazil

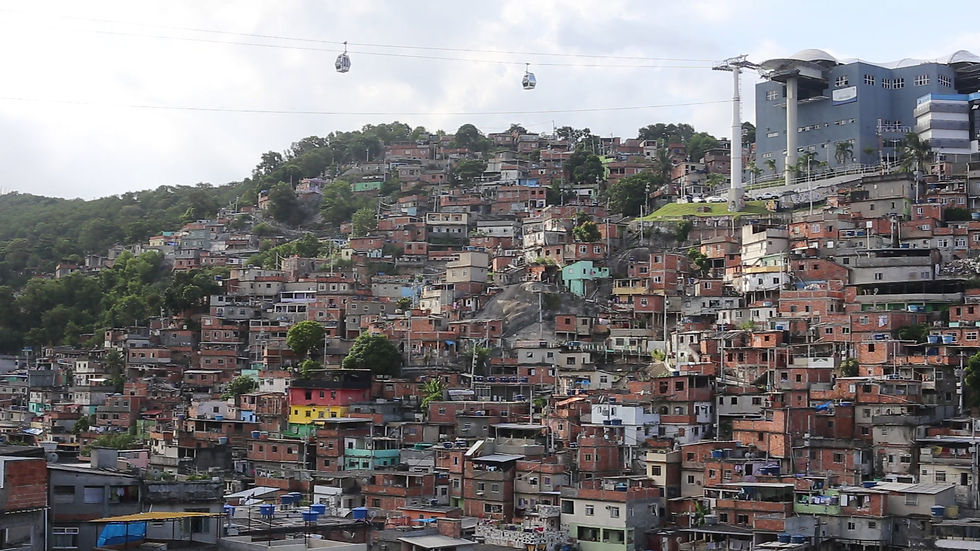

For my Doctoral Research (2010-2018), I lived with peace activists in several favelas (shantytowns) across Rio de Janeiro. I carried out 41 months of ethnographic research funded by a Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Fellowship and observed the implementation and subsequent failure of community policing programs. My research was particularly indebted to a group of young Afro-Brazilian social media activists from the favela who—in the lead-up to the 2016 Rio Olympics—used digital platforms to protest police violence and to partner with international digital inclusion NGOs. In 2022, I received Wenner-Gren Foundation funding for a collaborative project with three favela-born researchers that uses social media analysis and multimodal ethnography to examine Rio’s now abandoned community policing program.

WRITING ABOUT BRAZIL

Peer-reviewed Ethnographies

FAVELA STUDIES: A POROUS UNIVERSITY ON BRAZIL’S URBAN PERIPHERY."

2022

Brazilian favelas have been referred to as the most studied urban margins in the world. Noteworthy “favela studies” describe a porous urban entity that contests official definitions and popular prejudice. However, research about the favela consistently omits the work of local scholars and reflects an academic model akin to intellectual extraction. This article explores the potentials to center the favela through a critical reflection on the author’s long-term research carried out in the presence of university-educated resident-researchers who sought to build a university in the favela. Rather than simply adding to the number of “favela studies,” this article hopes to provoke greater support for a favela that studies both itself and a broader world. [subaltern urbanism, critical pedagogy, reflexivity, institutional analysis, postcolonial epistemology]

“DIGITAL FAILURES IN ABOLITIONIST ETHNOGRAPHY” IN SOCIAL ANALYSIS 65.1. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.3167/SA.2020.650108

2021

In an era when grassroots activism is defined by the use of social media, the democratic potentials of the Internet are constantly confronted by a shifting set of practical and political obstacles. Organizations seeking to abolish violent policing, for example, use social media to mobilize widespread support, but can fail to solidify lasting influence within government institutions. Similarly, twenty-first-century ethnographers have gained the ability to interact with grassroots organizations over social media, but often fail to gain insight into a movement’s internal politics or day-to-day struggles. This article focuses on the challenges of anti-violence activists in Brazilian favelas following the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics. The author explores how ethnographers can create a sense of continuity out of digital failure.

“MICROSOFT’S DRUG DEALER: DIGITAL DISRUPTION AND A CORPORATE CONVERSION OF FINES” IN TAPUYA: LATIN AMERICAN SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND SOCIETY.

HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1080/25729861.2020.1746501

2020

Over the last three decades, technology companies have promoted the “disruptive” potentials of the information age. Brazilian favelas (shantytowns) provide one of the most popular examples used to describe how digital disruption applies to informal urban communities. Favelas have been mapped by Google and surveilled by an IBM Smart City while hundreds of well-branded digital inclusion programs present themselves as alternatives to an informal economy and an illicit drug trade. However, corporate narratives of digital disruption fail to account for what scholars describe as an “insurgency” and practices of improvization (gato, jeitinho, or gambiarra) found in the favela. Describing a process of “converting” regulatory finesnes into well-branded social projects, this article provides an ethnographic account of a Microsoft-funded documentary about an ex-drug tra"cker turned digital educator. Considering the role of ethnography in an urban “gray zone,” this article asks: what techniques do global technology corporations use to take symbolic ownership of local knowledge? What does the dissonance between corporate and community-based narratives reveal about alternative forms of creativity in the digital age? And, how can we characterize the formalizing potentials of digital disruption in Latin America?

“UTOPIA DIGITAL: NGOS AND CONSUMER MARKETS IN BRAZIL’S “NEW MIDDLE CLASS” SHANTYTOWNS” IN

THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER CULTURE. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1177/1469540519890000

2019

This article examines how class, consumerism, and employment influence beliefs of an idealized digital world in marginalized communities. I recount 24 months of ethnographic and institutional observation in a non-governmental organization that promoted the concept of ‘‘utopia digital’’ (digital utopia in Portuguese) in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas (shantytowns). This corporate-funded non-governmental organization employed members of Brazil’s traditional middle class and promoted the liberating potentials of digital inclusion to members of a ‘‘New Middle Class’’ made up of 35 million ‘‘previously poor’’ Brazilians. Interviews with middle-class employees reveal how ideas of digital utopia act as a code for corporate efforts to encourage consumerism among the New Middle Class and bolster employment opportunities for members of Brazil’s traditional middle class. Reflecting on informal conversations, I also highlight a middle-class ‘‘crime talk’’ that frames the favela as an inherently violent place and, in contrast to their inclusionary work related to digital utopia, encourages non-governmental organization workers to physically avoid favela space. I use Zygmunt Bauman’s discussion of an ‘‘active’’ or ‘‘hunter’’ utopia as an ethnographic lens to discuss the practical and everyday experiences of technological inclusion in classed settings. By describing digital utopias as actively shaped by everyday understandings of urban exclusion and privilege, this article provides an ethnographic framework for decoding the socially reproductive nature of class-inflected consumer interventions in marginalized communities.

“DEATH ON REPEAT: VIOLENCE, VIRAL IMAGES, AND QUESTIONING THE RULE OF LAW IN BRAZILIAN FAVELAS” IN THE JOURNAL OF LEGAL ANTHROPOLOGY. VOLUME 3, ISSUE 1: 21–40.

2019

In the past decade, images of fatal police shootings shared on social media have inspired protests against militarised policing policies and re-defined the ways marginalised communities seek justice. This ar¬ticle theorises the repetition of violent images and discusses how social media has become an important tool for localising popular critiques of the law. I provide an ethnographic account of a police shooting in a Brazilian favela (shantytown). I am particularly interested in how residents of the favela interpret law and justice in relationship to contemporaneous move¬ments such as Black Lives Matter. Reflecting Walter Benjamin’s concept of mechanical reproduction, this case study demonstrates an ‘aura’ that is shaped by the social and legal context in which a violent image is pro¬duced, consumed and aggregated. This case study suggests the possibility for research examining the ways inclusionary social media platforms are increasingly co-opted by oppressive political institutions.

“PACIFIED INCLUSION: DIGITAL INCLUSION IN BRAZIL’S MOST VIOLENT FAVELAS” IN URBAN SOLUTIONS: METROPOLITAN APPROACHES, INNOVATION IN URBAN WATER AND SANITATION, AND INCLUSIVE SMART CITIES. WOODROW WILSON CENTER URBAN SUSTAINABILITY LABORATORY. 105-122

2016

Starting in 2008, the city of Rio de Janeiro began to “pacify” its gang-ridden favelas and invest billions of dollars in economic development. Pacified favelas became more integrated within the broader Brazilian political system while innocent bystanders fell victim to daily police-trafficker shootouts. During this time, digital technology became a ubiquitous tool for favela activists who sought to critique pacification policy as a reproduction of structural inequalities. The discussion of violence helped to form a network between online favela activists and powerful institutions in the Brazilian state. This network embraced participatory politics in the form of Paulo Freire’s ideas of “critical pedagogy” as well as state-aligned ideas of entrepreneurship and economic formalization. The friction between state- and community-oriented goals in Rio’s favelas demonstrates that structural violence is an essential aspect of how communities experience digital inclusion.

"PEACE PROFILE: RENE SILVA." PEACE REVIEW 33, NO. 1 (2021): 155-163.

2021

Few social media activists have had as large of an influence as Rene

Silva, a 27-year-old from Rio de Janeiro’s most notorious group of favelas

(shantytowns) known as the Complexo do Alem~ao. At the age of 11,

Silva founded a community newspaper called Voz das Comunidade

(Voice of the Community). By 2020, the paper had a monthly circulation

of 20,000 and Silva had hundreds of thousands of followers on social

media. Silva has various accomplishments outside of journalism including

partnering with multinational corporations to bring clean drinking water

to his community and helping to organize thousands-strong protests

against deadly police policies. For invested observers of Brazilian social

movements, Rene Silva is the archetype of a millennial activist.

I met Rene Silva in 2014, as I began a long-term ethnographic